The European Union towards its strategic autonomy

The EU international agenda has sometimes lacked strategic autonomy when dealing with an ever-changing global scenario. This has diminished the EU’s ability to have a say in the set-up of a new global order. As we will see, several factors have contributed to this situation and further steps need to be taken to foster the EU’s strategic autonomy.

US extraterritoriality: a main threat against EU strategic autonomy

The EU has rarely been able to contradict the hegemonic aspirations of its preferred partner, the US. Washington has always relied on a powerful foreign policy instrument, the extraterritoriality, that is, the ability of the US to interfere with European sovereignty, mainly in economic and global trade affairs. Consecutive US Administrations have made use of a legislative and discursive bricolage especially designed for giving a legal and legitimate appearance to US extraterritoriality. This practice, in my opinion, must be regarded as a form of lawfare. Lawfare can be defined as “the strategy of using – or misusing – law as a substitute for traditional military means to achieve an operational objective” (Dunlap, C. J., 2008: 146). However, US extraterritoriality has also an economic foundation. The US Dollar has a privileged position in the global economy as the world’s most important international reserve and trade currency, subordinating the EU and its currency (Sanahuja, 2008: 359).

Given this situation, Brussels should commit itself to upgrading its role as a global actor in order to have a say in the shape of a new global order.

Some recent EU foreign policy initiatives against US extraterritoriality

The EU has some experience in developing foreign policy initiatives against US extraterritoriality. Most of them were ad hoc instruments, but some have proven their usefulness. The new EU Commission (EC), even more than the former one, is well aware of all the challenges and is currently upgrading the old tools and creating new ones. Two initiatives have been chosen to be analysed because of their topicality, and some conclusions will be drawn from their scrutiny.

Upgrading Old Tools: The Blocking Statute

The Blocking Statute was the first sensu stricto mechanism developed by the former European Community in order to deal with US extraterritoriality.

Back in 1996, the US issued a legislative package with an extraterritorial scope consisting of the D’Amato-Kennedy Act and the Helms-Burton Act. Under the D’Amato-Kennedy Act, sanctions were imposed to the Rogue States (mainly, Iran and Libya), “as a result of their support to the international terrorism and their will to develop weapons of mass destruction”. According to the Helms-Burton Act, US courts were allowed to adjudicate trade and economic relations between foreign companies and Cuba, when all the circumstances described in its Title III occurred.

At that time, the European Community was conducting an improvement of the bilateral relations with Castro’s Cuba. Brussels rejected the extraterritorial scope of the US legislation, as it did not respect International Law and was against the agenda of the EC. Thus, the EU decided to take action. In October 1996, the EC adopted the Regulation 2271/96, also known as “the Blocking Statute”, through which they sought to bypass the extraterritoriality of this legislation. Regulation 2271/96 was in line with other measures adopted by Canada or Mexico.

Years later, in 2018, the US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPoA) implied the reintroduction of trade restrictions to Iran, as well as to European companies trading with Iran, and the subsequent end of Iran’s promise not to develop a military nuclear programme; a big setback to the EU diplomacy. In response, the EU adopted the Delegated Regulation 2018/1100, which updates and resumes the Blocking Statute.

The so-called Blocking Statute operates in a double way. Firstly, it cancels out the effects of foreign court rulings based in an extraterritorial law and, therefore, it forbids EU companies to abide by the sanctions resulting from those rulings; and, secondly, it allows EU operators to claim compensation for damages that may arise from the implementation of an extraterritorial legislation. Nevertheless, the Regulation also introduces the possibility for EU persons to request an authorisation to abide by this extraterritorial law as long as it could result in a grave prejudice to their interest.

The major weakness of the Blocking Statute is the fact that it has never been actually used. This is due to the lack of clarity of the guidelines that the EU defined. Moreover, it is almost impossible for EU authorities to prove that an EU company has decided to interrupt its economic transactions with the target country because of the existence of US sanctions against that country instead of mere economic reasons or changes in its industrial or trade strategy. In this regard, large EU companies with great interests in Iran, such as Airbus, Total, Siemens, the PSA group or SWIFT have decided to comply with US sanctions, as they found it better than the uncertainty arising from current EU law (De Ruyt 2019: 2).

Creating New Tools: The Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX)

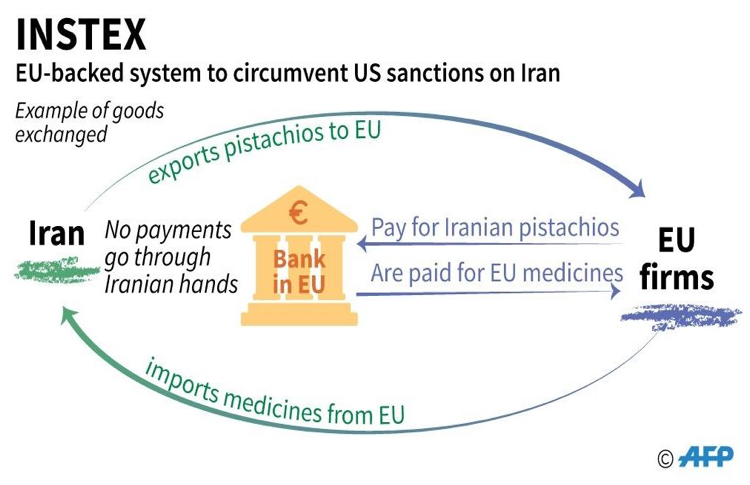

After the reintroduction of US sanctions, the EU started working on a solution to maintain the trade flow with Iran and, thus, keeping Teheran within the nuclear deal framework. The main threat to the EU-Iran trade flow is the US ability to legally or factually control financial transaction systems. This ability is founded on its dominant position on the global market and the hegemony of the dollar.

In September 2018, Federica Mogherini, former High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, announced that negotiations for the development of a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) were taking place. In business law, a SPV is a subsidiary created by a parent company to isolate potential financial risk. This particular SPV is designed to facilitate legitimate trade operations with Iran and, thus, to alleviate the flaws of the Blocking Statute.

In January 2018, France, UK and Germany (the E3), with the support of the European Commission and the European External Action Service (EEAS), created this new financial institution. The INSTEX is headquartered in Paris and, besides the E3, its current shareholders are Finland, Belgium, Denmark, Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. China and Russia have also shown interest, but no public statement has been issued from Brussels so far.

The INSTEX works as a non-USD and non-SWIFT clearing house. It would allow a European goods exporter to Iran to be paid by a European goods importer from Iran. With this method, the transactions would stay out of the reach of the US control over global money transfers as they are kept within European and Iranian borders. It would thus not be necessary to resort to commercial banks who fear restrictions on their operations on the US financial market. For now, the INSTEX focuses only on the most essential sectors for the Iranian population, which are not affected by US sanctions, as agri-food, pharmaceutical or that of medical devices, leaving aside the oil sector. This limitation is intended to avoid a violent reaction from the US.

Source: Agence France-Presse.

The INSTEX is currently available to any EU economic operator since Iran already launched its counterpart in April 2019, the Special Trade and Financial Instrument (STFI) (Iran Chamber of Commerce, 2019). However, Teheran has expressed concerns about this instrument and the real European political will (The Guardian, 2019). Even though the first transaction was conducted, it was just a shipment of medical goods produced by a German company, whose value was less than a million euro. Moreover, the current political scenario has become quite fragile: after the assassination of Qasem Soleimani, Ayatollah Khamenei’s right-hand man, and the subsequent reaction by the Iranian government, the E3 has recently lodged a formal complaint by triggering the dispute resolution mechanism contained in the JCPoA in order to bring Iran back into full compliance with its commitments.

Conclusion

As gathered from all the above, Brussels is gradually performing riskier moves in the global scenario and, therefore, broadening its experience in this field. This proves that the EU is relatively committed to a sovereign foreign policy in terms of external actions. There is also an institutional commitment, as it can be inferred from the new EU Commission’s decision to move the sanction enforcement unit from the EU High Representative to the Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union (FISMA) in order to achieve a more stringent implementation of EU sanctions.

However, the EU has still a long way to go in order to fully develop its strategic autonomy in this particular matter. One challenge certainly is that the Member States still have the final say and many of them lack the political will, as the consequences from facing US extraterritoriality can threaten their short-term agendas.

Bibliography

Citroën C. A. (2019), ‘Comment gagner la guerre de l’extraterritorialité ?’, Le Grand Continent. Available at: https://legrandcontinent.eu/fr/2019/06/19/comment-gagner-la-guerre-de-lextraterritorialite/ (Accessed: 1 March 2020)

Dall, E. (2019), ‘A New Direction for EU Sanctions: The New Commission and the Use of Sanctions’, Commentary, Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). Available at: https://www.rusi.org/commentary/new-direction-eu-sanctions-new-commission-and-use-sanctions (Accessed: 1 March 2020)

Del Arenal, C (2009), ‘Mundialización, Creciente Interdependencia y Globalización en las Relaciones Internacionales’, Cursos de Derecho Internacional y Relaciones Internacionales de Vitoria-Gasteiz 2009.

De Ruyt, J. (2019), ‘American Sanctions and European Sovereignty’, nº 54, European Policy Brief, Egmont Royal Institute for International Relations. Available at: http://aei.pitt.edu/97376/ (Accessed: 1 March 2020)

Dunlap, C.J. (2008), “Lawfare today: a perspective”, Yale Journal of International Affairs, vol. 3. Available at: https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/faculty_scholarship/3154/ (Accessed: 21 March 2020)

Dwyer, C. (2020), ‘‘Left with no choice’, European Allies put Iran On Notice Over Nuclear Deal Breaches’, NPR (online), 14 January. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2020/01/14/796199041/left-with-no-choice-european-allies-put-iran-on-notice-over-nuclear-deal-breache (Accessed: 1 March 2020)

Geranmayeh, E., Rapnouil, M. L. (2019), ‘Meeting the challenge of secondary sanctions”, Policy Brief, European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR). Available at: https://www.ecfr.eu/page/- /4_Meeting_the_challenge_of_secondary_sanctions.pdf (Accessed: 1 March 2020)

Lamy, P., Bérard, M.H., Fatah F., Schweitzer, L., Vimont, P. (2019), ‘EU and US Sanctions: Which Sovereignty?’, Policy Paper nº 232., Institut Jacques Delors. Available at: https://institutdelors.eu/en/publications/leurope-face-aux-sanctions-americaines-quelle-souverainete/ (Accessed: 1 March 2020)

Sanahuja, J.A. (2008), ‘¿Un mundo unipolar, multipolar o apolar? El poder estructural y las transformaciones de la sociedad internacional contemporánea’, Cursos de Derecho Internacional de Vitoria-Gasteiz 2007.

Wintour, P. (2019), ‘Iran says progress made in nuclear talks is still not enough’, The Guardian (online), 28 June. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/28/world-powers-iran-nuclear-deal-abandoned-us (Accessed: 1 March 2020)

Sauerbrey, A. (2020), ‘The Failure of Europe’s Feeble Muscle Flexing’, The New York Times (online), 10 February. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/10/opinion/europe-iran-nuclear-deal.html (Accessed: 1 March 2020)

Ignacio Escondrillas

Ignacio Escondrillas is a young professional working as a trainee at the Spanish Embassy in Argentine.